NEWS

9 Dec 2025 - Performance Report: Bennelong Emerging Companies Fund

[Current Manager Report if available]

9 Dec 2025 - Performance Report: 4D Global Infrastructure Fund (Unhedged)

[Current Manager Report if available]

9 Dec 2025 - News and Views: The impact of a steeper yield curve on global listed infrastructure

|

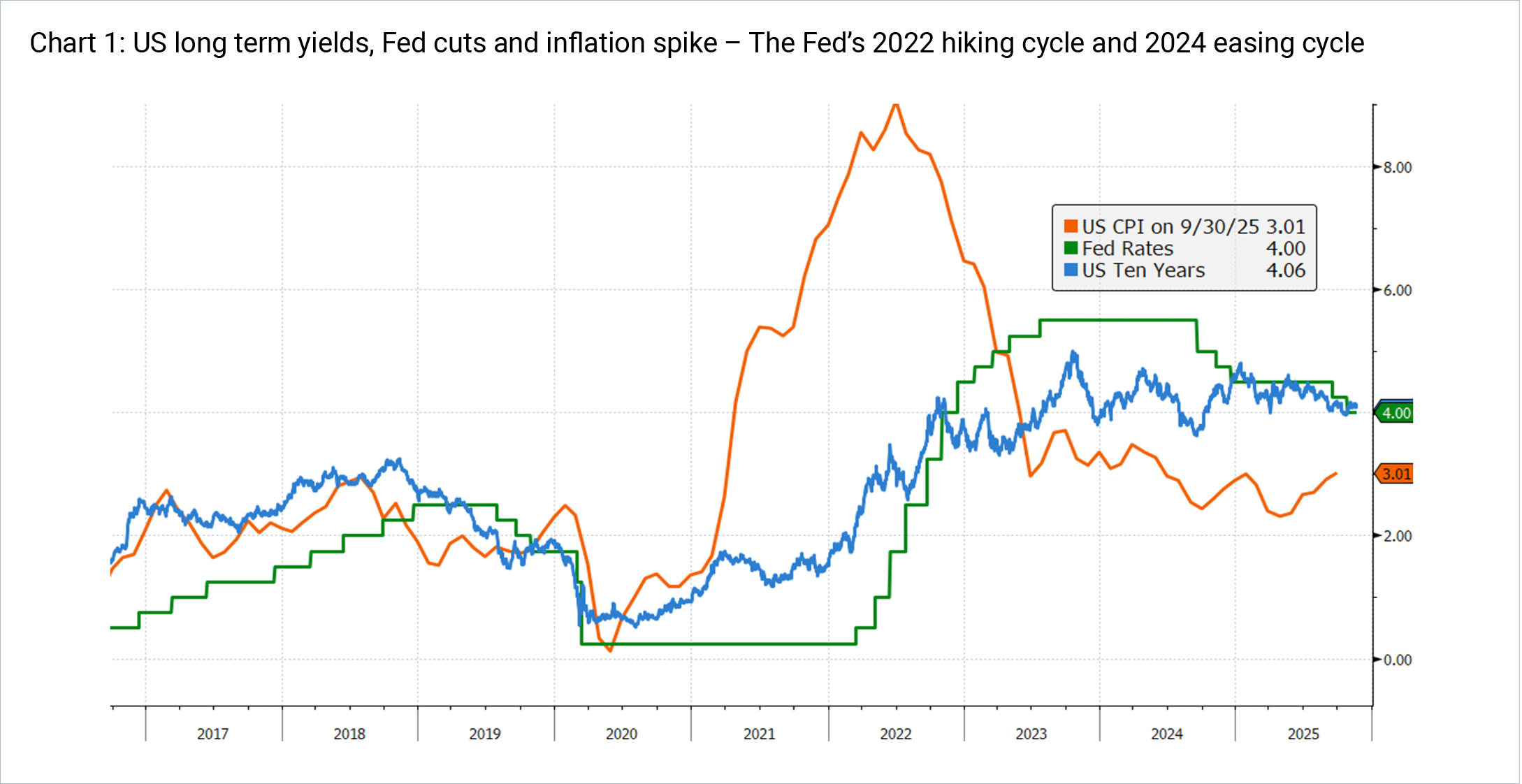

News and Views: The impact of a steeper yield curve on global listed infrastructure 4D Infrastructure December 2025 15-minute read Utilities and infrastructure valuations, typically sensitive to long-term yields, have been challenged by an exceptional rise in US bond yields despite significant Fed rate cuts, prompting an examination of the drivers, sustainability, and implications of this move for global listed infrastructure sectors. Utilities and infrastructure companies own very long dated assets characterised by high up front capital costs and returns often correlated to economic parameters. As such their valuations can be sensitive to changes in long term bond yields, some sectors more than others. The sharp inflation spike of 2021-22 led the US Fed to raise rates at a record pace, from 0.25% to 5.5% over 18 months, representing a headwind for certain segments of the infrastructure universe, particularly US utilities (no explicit inflation or interest rate pass through). Positively, this Fed action reigned in inflation and market expectations turned to Fed cuts. The subsequent easing cycle, commencing in September 2024, was expected to be a tailwind for infrastructure and in particular for utilities that have strong fundamental linkages to interest rates. While Fed interest rate cuts of at least 25bps generally coincide with a decline in long term bond yields this easing cycle has proved to be an anomaly: the Fed has cut by a cumulative 150bps and US ten-year yields have risen by ~50bps. In this News & Views we investigate what has driven this increase, if it can be sustained and the outlook from here. Finally, we then assess the impact this has on global listed infrastructure (GLI) valuations and how 4D manages these risks and opportunities. Bond yields - short & long term, components & moves after Fed cutsShort term yields are mainly driven by central bank policy rates and near-term inflation and growth expectations. By contrast, long term yields reflect expected future short-term rates as well as longer-run views on inflation, growth and a 'term premium' for compensating investors for the risk of holding longer dated bonds. Specifically, recent studies on the parameters affecting bond yields across maturities point to two key components:

As an infrastructure investor, the level and direction of long term yields are more important to us than short term moves as they have the largest impact on valuations, portfolio construction and risk management. As mentioned above, the inflation spike from very loose COVID monetary and fiscal policies led to a very steep Fed rate hiking cycle in 2022. The subsequent fall in inflation from above 9% to towards the Fed's 3% target led to the shifting of market expectations to an easing cycle.

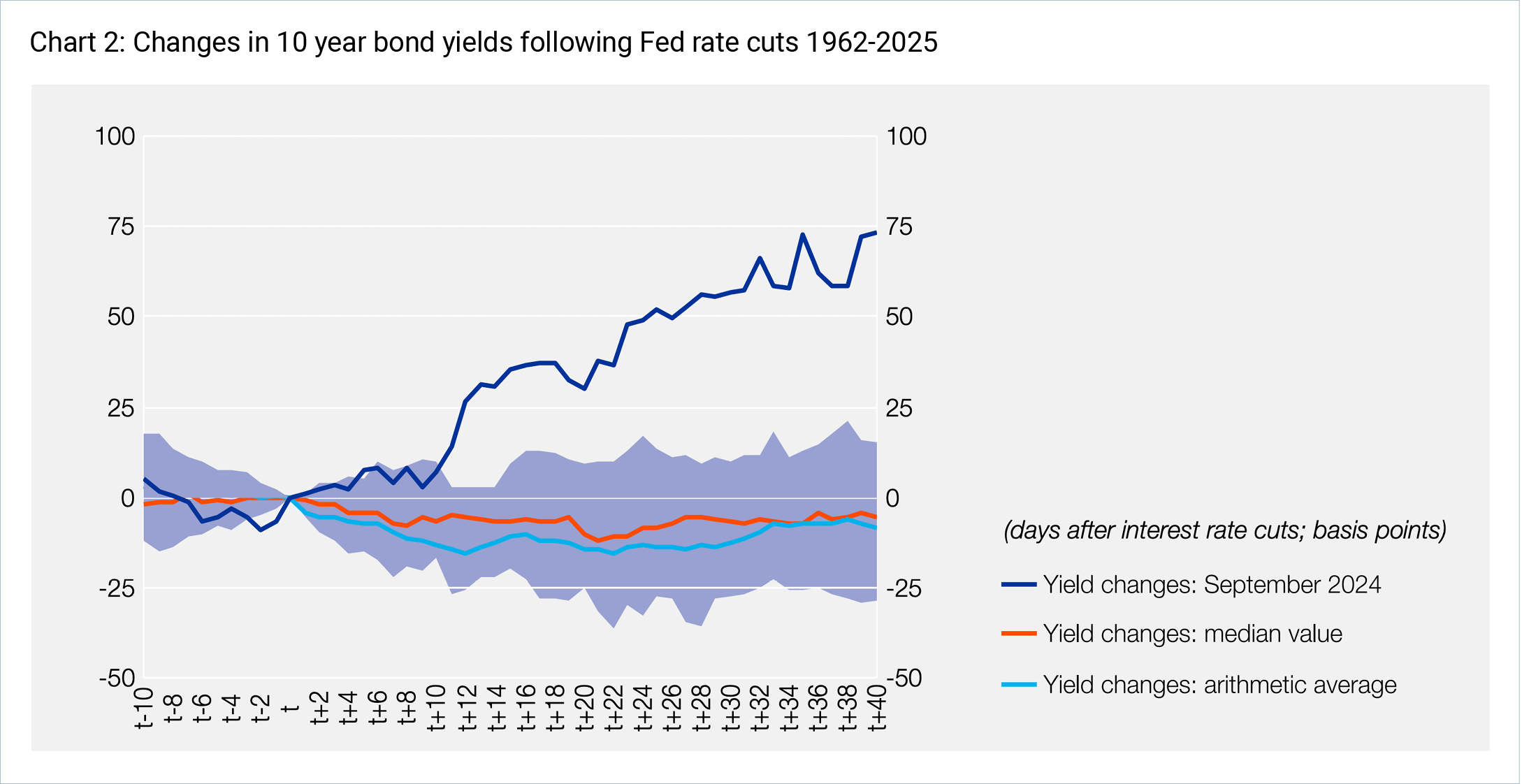

According to central bank research, since the 1960s Fed cuts of at least 25bps are followed by an average decline in long term bond yields of 10-16bps over the following calendar month, before stabilising at the lower level.2 This can be seen in the lower blue and red lines in Chart 2 below.

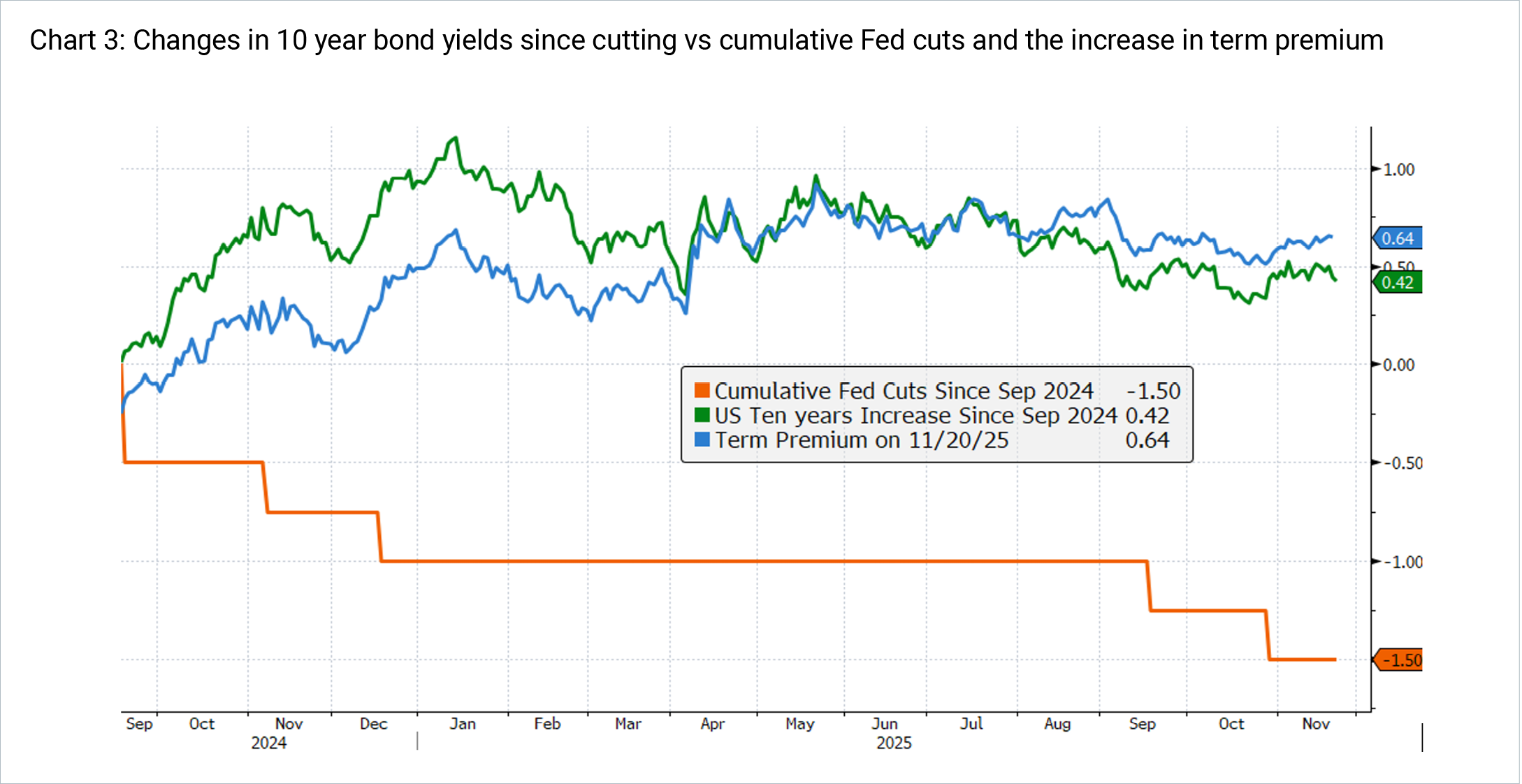

The market movements since the Fed started cutting in September 2024 have been very different to the historical price action seen above. As can be seen in Chart 3, as at November 2025 the Fed has cut 150bps while 10 year yields have increased 42bps. This move is rare - with this level of increase in the upper 10% of historical observations in the chart above, where the dark purple shaded area is the 25%-75% range of observations in the distribution.

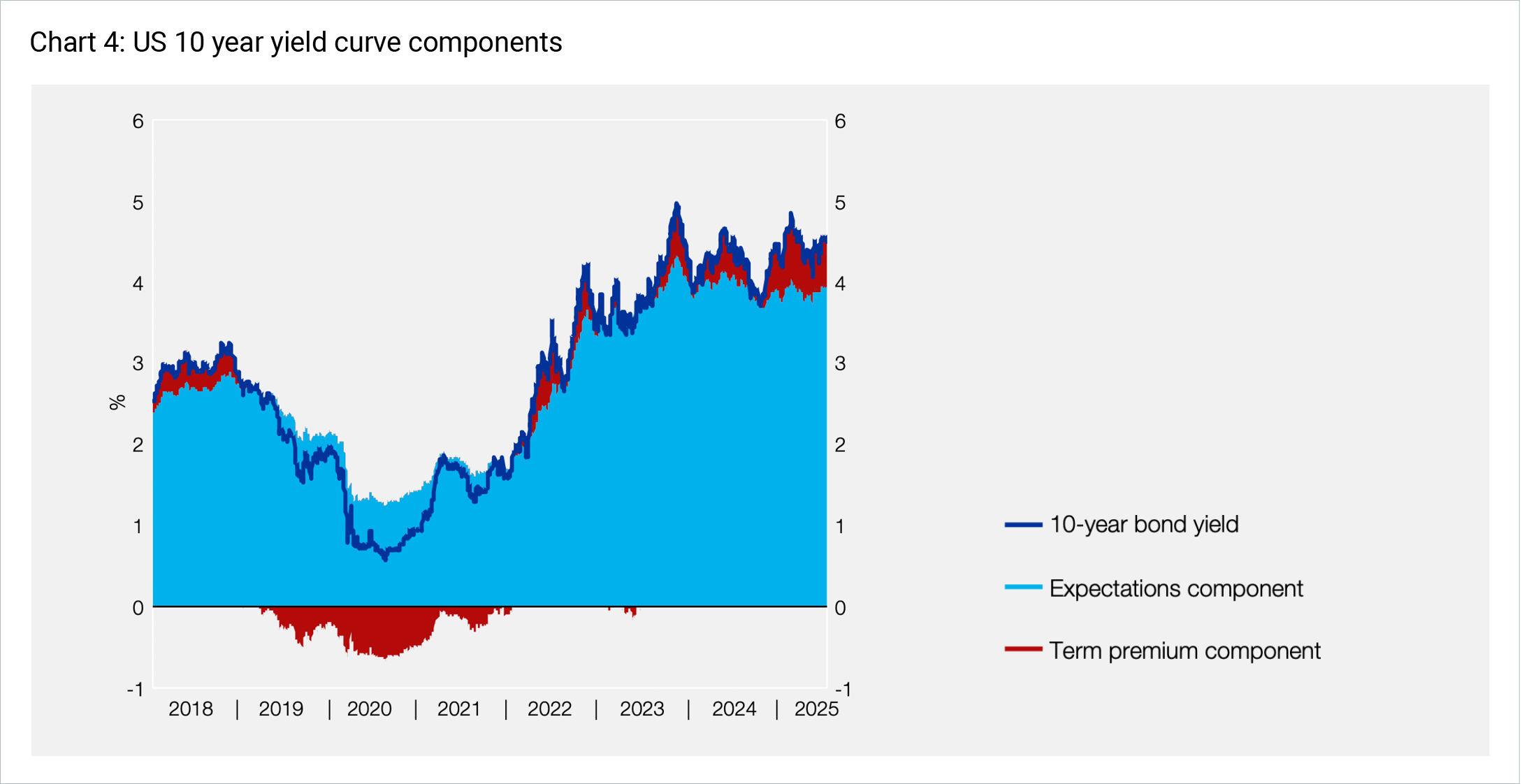

In order to investigate the reasons for the long bond yield increase, we can split up the components of the yield into its expectations component and term premium (explained above). We can see that over this recent period, the expectations component was largely stable (the light blue in Chart 4).

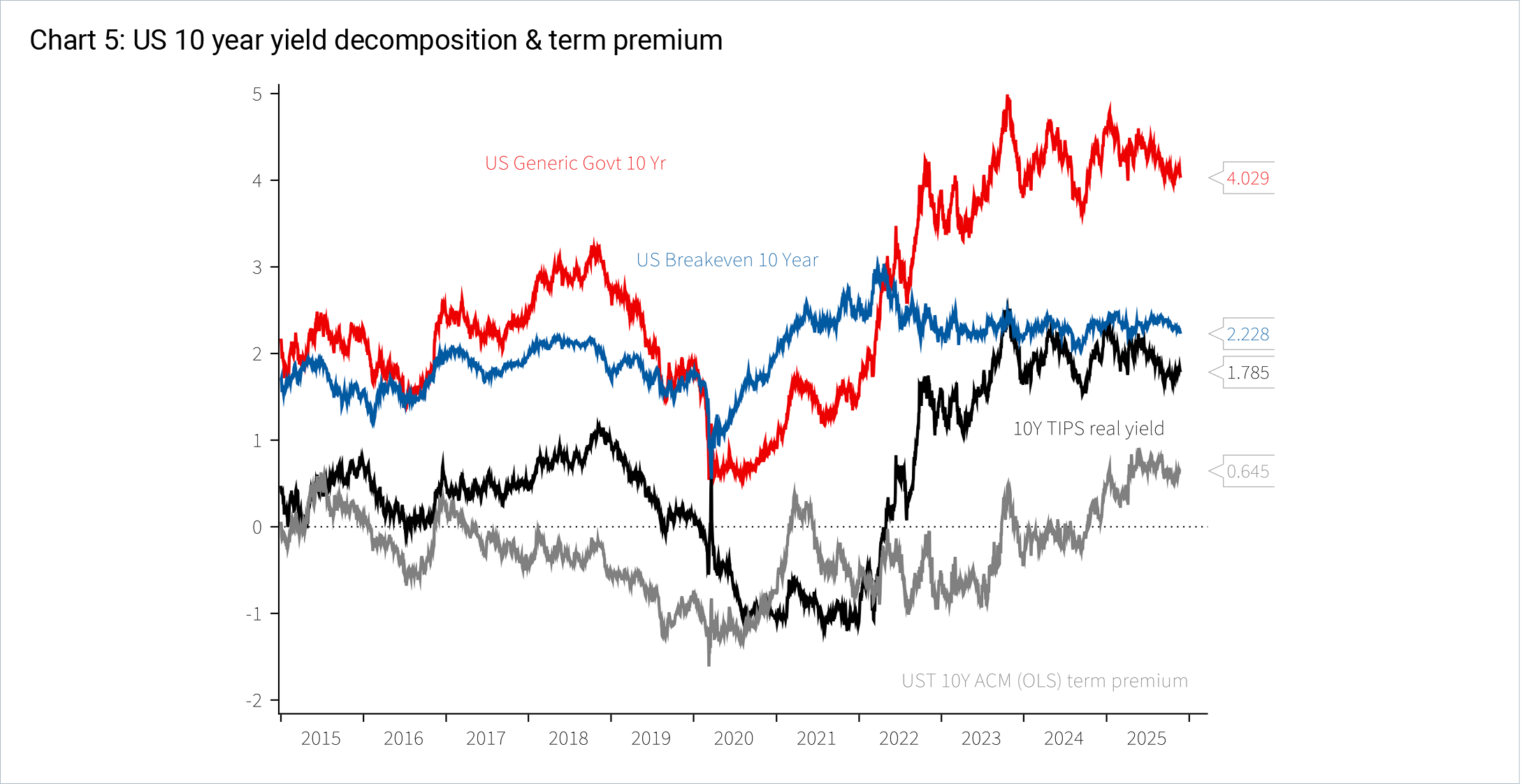

Furthermore, as can be seen in Chart 5, inflation expectations have stayed broadly stable too, indicated by the US breakeven below in blue.

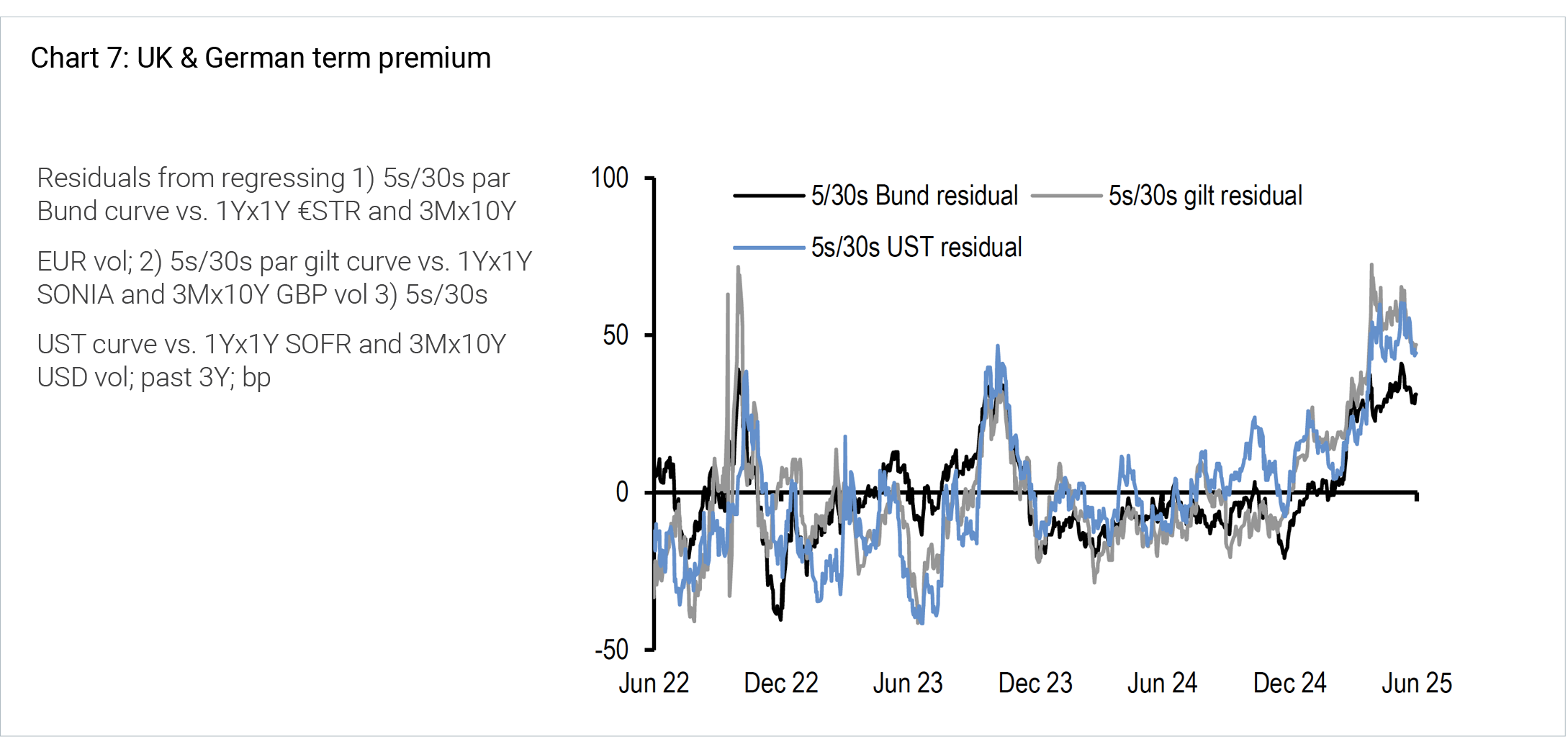

This implies that an increase in term premium has caused a steepening of the yield curve, despite short rates dropping since September 2024. The term premiumOver 2025 there has been a lot of debate among central bankers, academics and market participants, as to the cause of the increase in term premiums by 50-100bps since the Fed's easing cycle began in 2024. Arguments include:

Other reasons for a steepening in the curve:

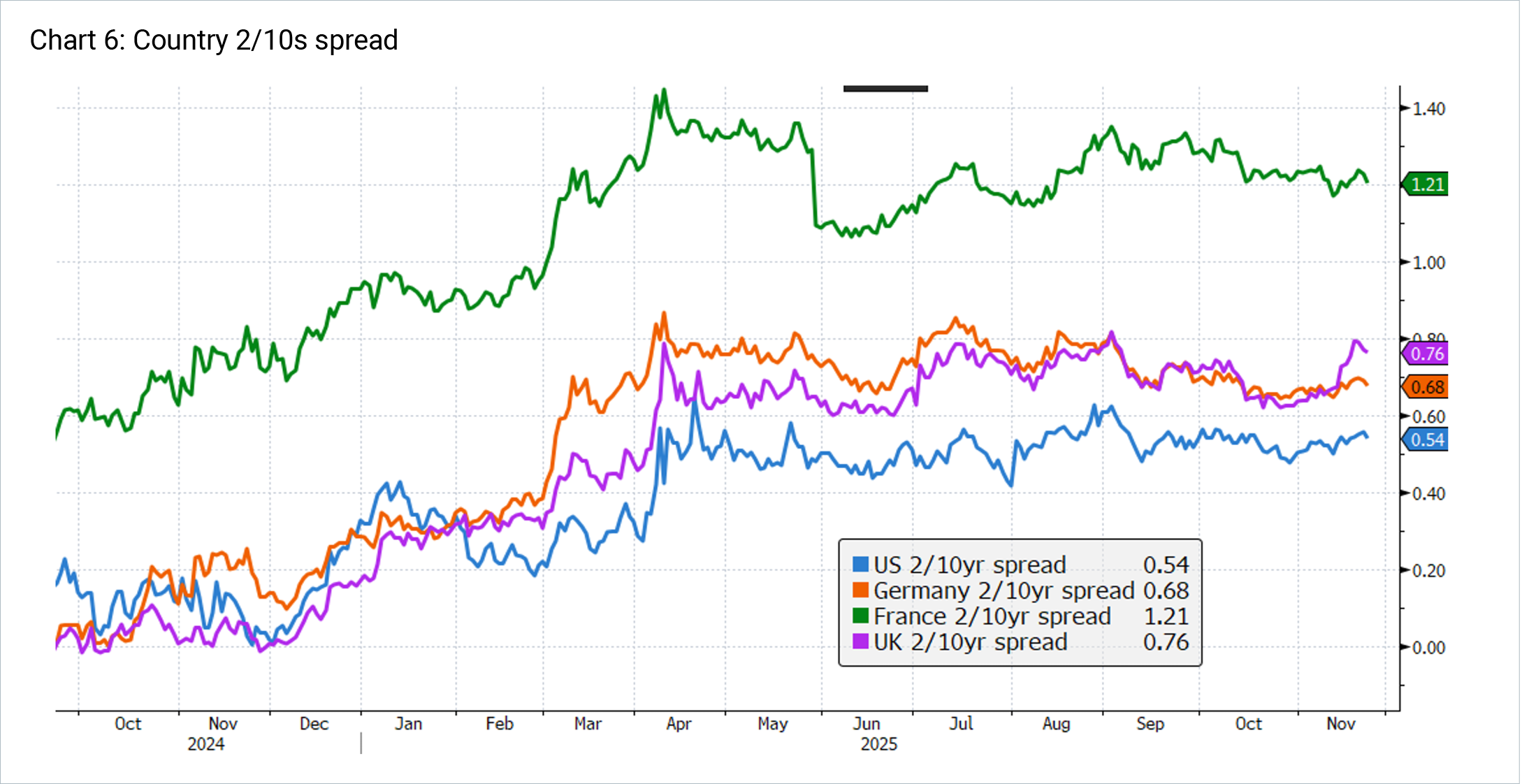

US Fed Governor Michelle Bowman summed up another risk of higher yields brought on by higher term premiums in a speech on 26 September 2025: Term premiums...A second challenge for monetary policy would be a significant rise in longer-term interest rates driven by higher term premiums, which could offset a reduction in the expectations component stemming from monetary policy easing. This scenario would weaken the transmission of changes in the policy rate to economic activity, as investment decisions of households and businesses are dependent on longer-term rates, such as mortgage rates and corporate bond yields.5 While the term premium has risen sharply, and many are looking for reasons why, it is worth noting that it remains below levels that persisted prior to the GFC. As JP Morgan note, "while this is a big move, it is not unexpected: term premium has retraced closer to average levels observed in the decade prior to the GFC, and does not seem to be unduly high in our opinion right now. Moreover, the demand for longer duration assets seems to be receding globally now as well". Transmission mechanism to the rest of the worldThe steeper yield curve has not been isolated to the US. As seen below, German, French and UK yields have also been steepening over the last 18 months - evidenced by the spread between the 2 and 10 year yields. Part of this has been the linkages in sovereign debt markets with the US, while other drivers are country specific. These all include common traits of worsening debt metrics and political impasse:

Likewise, JP Morgan analysis estimates the term premium for these economies, despite fiscal idiosyncrasies between them, remain well correlated.

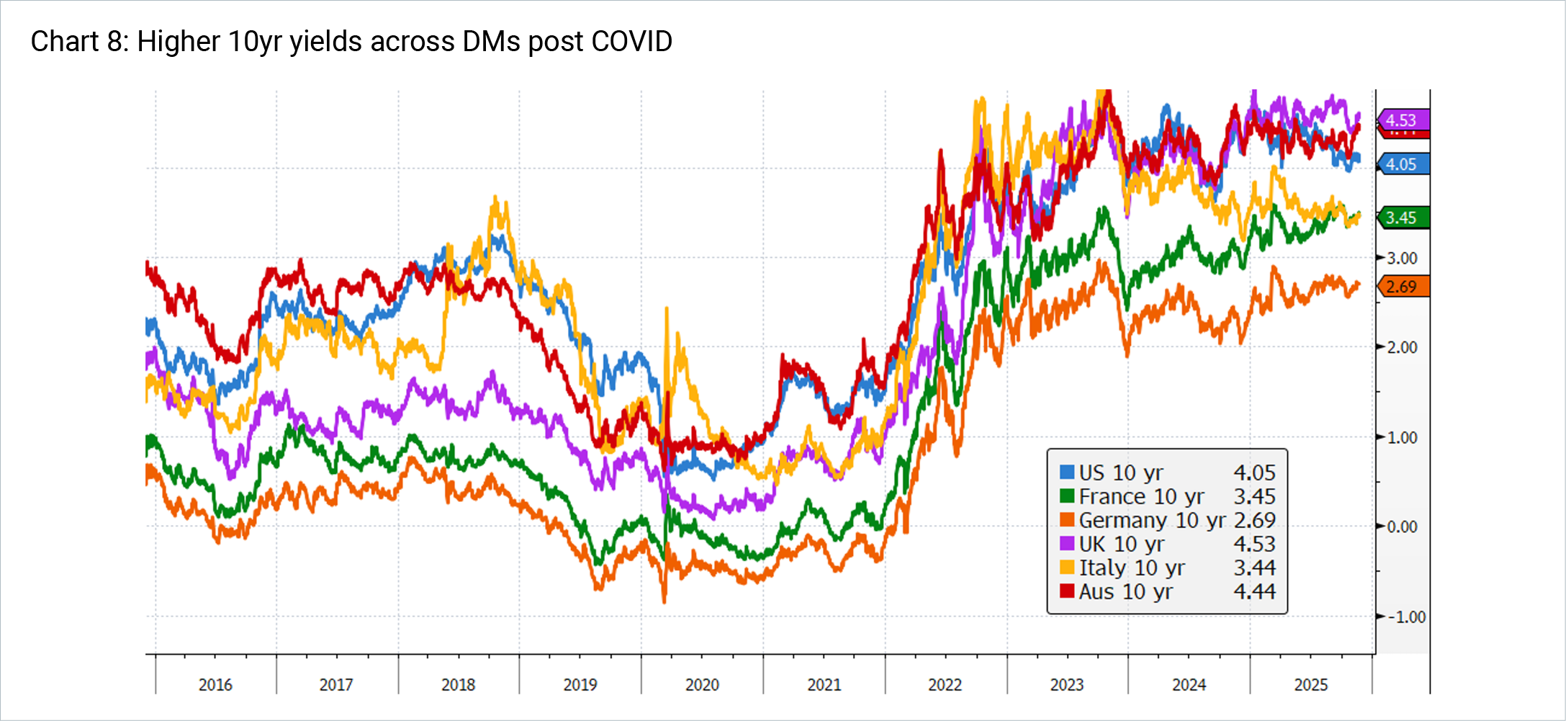

At an absolute level, long bond yields across developed economies remain higher than pre-COVID. In part this is because of higher long run neutral rates (known as r*), due to structurally higher inflation expectations (less global slack), as well as larger government deficits, higher investment needs and more issuance.

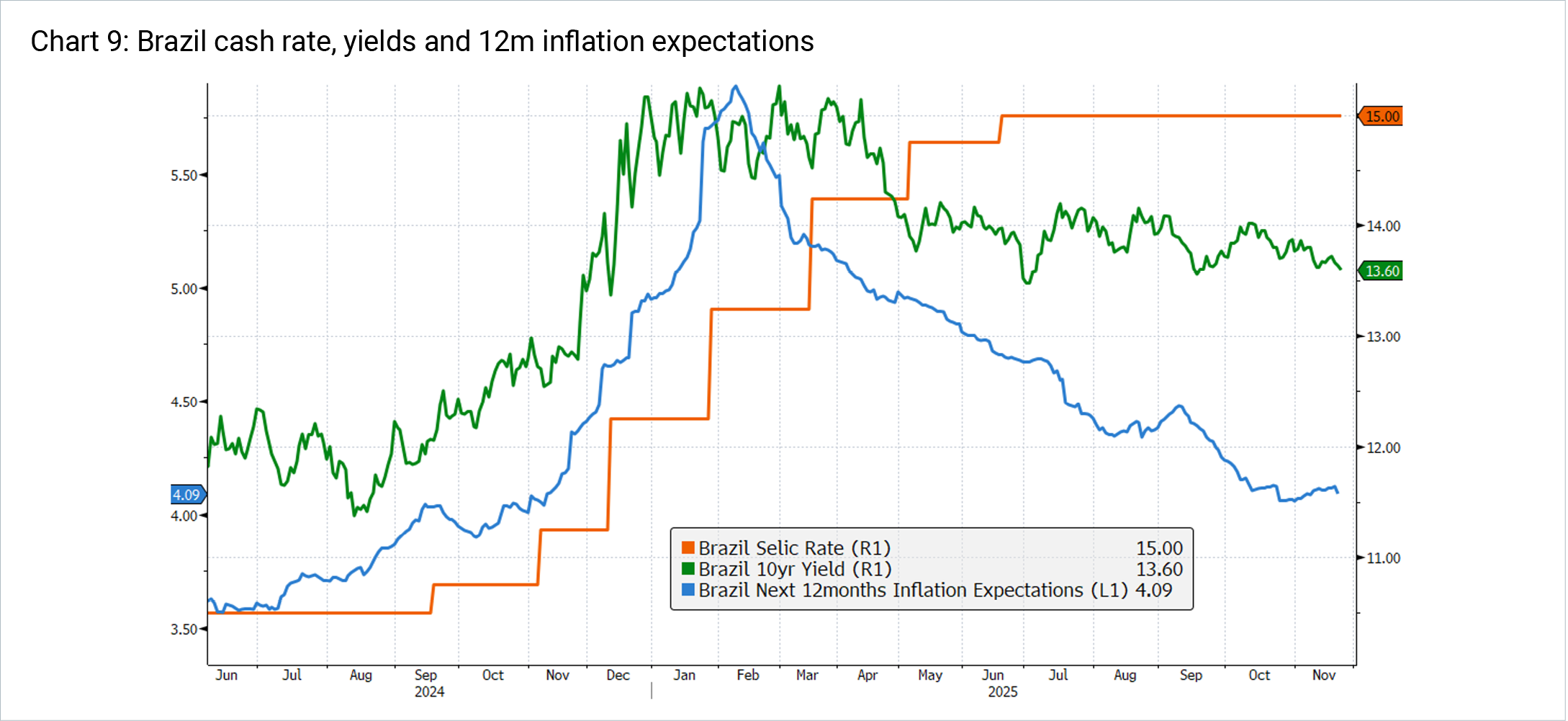

By contrast, Brazil has reported the opposite moves in short term cash rates and long term yields. From mid 2024 the central bank aggressively raised the SELIC rate 450bps to 15% to combat rising inflation expectations due to market expectations of lower government fiscal discipline and constraint around annual budget planning. This aggressive hiking cycle, while painful, also aimed to cool strong domestic economic growth. To date this has proved successful, with inflation expectations coming back down towards the target range. Since the start of 2025 cash rates are up 275bps and 10 year yields have actually fallen 120bps. A key reason for this, according to Bloomberg's Brazilian Economist, is the ultra hawkish approach has actually given the central bank a credibility boost, which has reduced the risk perception and lowered inflation expectations. Looking at the 5 year rate, which declined to 13.2% from 15.5% at the start of the year (even as policy rates rose 275bps), Bloomberg states that their "model attributes 150bps of the cumulative 240bp drop to an improvement in risk factors. In our view, this largely reflects reduced concerns over monetary policy making under Gabriel Galipolo, who became central bank governor in January for a 4 year term" 6

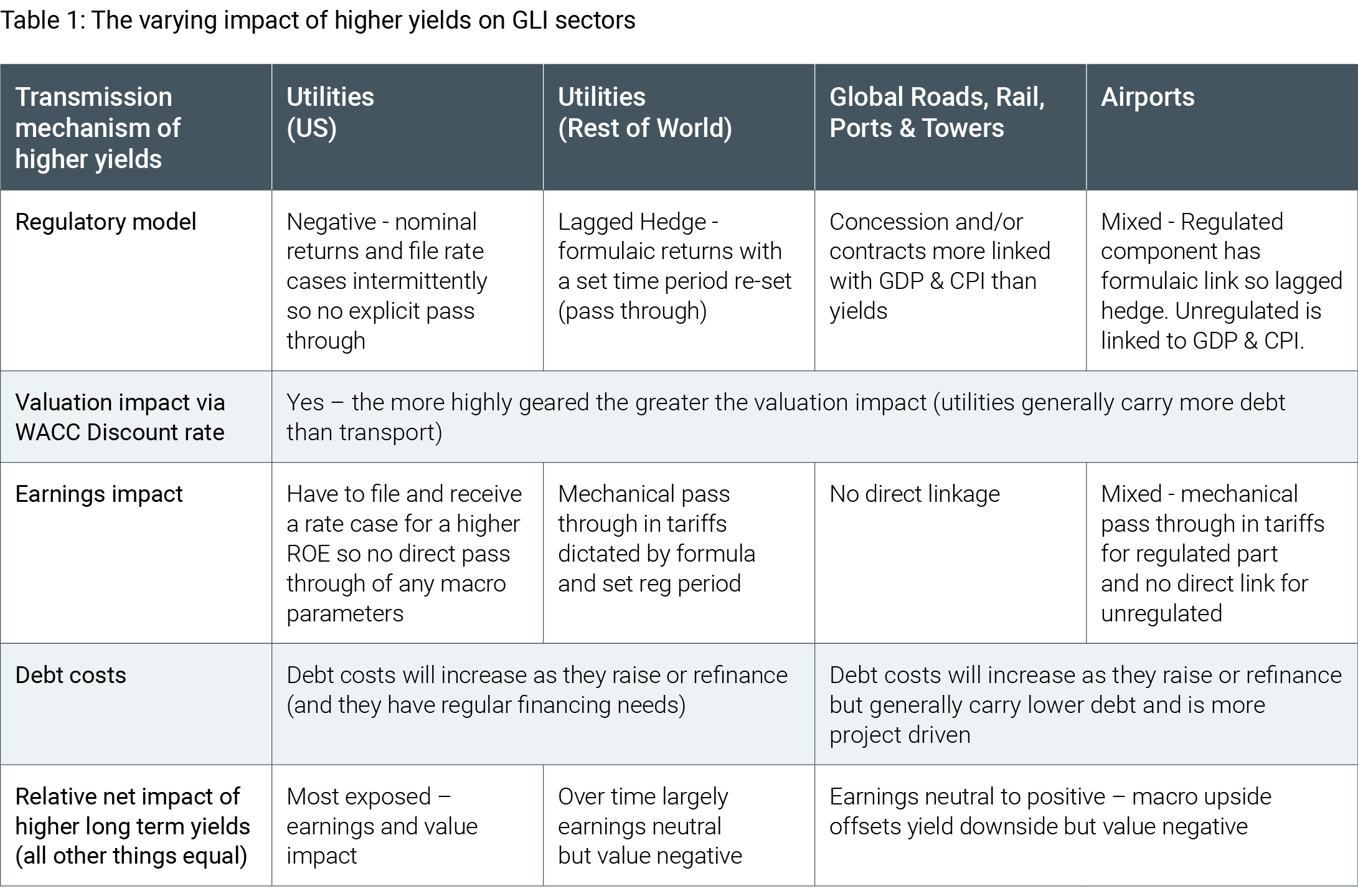

Why this matters - the relationship between infrastructure values and yieldsAt 4D, we use long bond yields to discount the cashflows from these long duration assets. Therefore, a steeper curve - as well as a permanently higher curve - has an impact on valuations of infrastructure assets as a simple function of discount rates. It also impacts fundamental cash flow modelling through forecast regulated return profiles, inflation expectations and borrowing costs, as well as the ability to borrow. In very general terms, it has a greater impact on the utility segment relative to other sub-sectors due to its greater correlation to economic indicators like government yields (as a building block of regulated returns) and in some cases inflation. This is where stock and sector selection within the GLI universe becomes crucial, and a truly active approach to investing is highly valuable. Across the global infrastructure universe 4D has the ability to shift between geographies and sectors where there is more or less sensitivity to long bond moves (both steepness and level of change) and look for exposures that can fundamentally capitalise on moves better than others - as well as exposures with greater ability to pass through inflation, serving to mitigate the impact of higher rates alone.

Also, ignoring sentiment and historic correlations, a number of sector dynamics are supporting fundamental growth outside historical long term yield dynamics. This is particularly relevant for the utility sector which is undergoing a seismic shift in investment mandates to support AI and data centre themes (US) and/or network upgrades to support energy transition and replacement spend (Europe). As such, the historic tight correlation of utility share price performance with yields is potentially no longer warranted, as seen in Chart 11 from early 2024.

ConclusionOne must be careful not to naively assume the Fed's easing cycle is a slam dunk for long duration assets such as utilities and infrastructure assets. The long end of the curve drives GLI valuations more than the short end, and since the Fed started cutting rates in 2024 we have witnessed something rare by historical standards - an increase in long term yields. This has been driven by an increase in the term premium, due to increased political and economic uncertainty, worsening debt metrics, long term budget outlooks and supply-demand dynamics. At 4D we monitor these risks and construct and actively manage a portfolio to balance the risks and opportunities across geographies and sectors. Furthermore, with an active approach to portfolio construction, we can target exposures with idiosyncratic drivers of earnings growth to offset these factors, such as those seen in the networks businesses globally.

The content contained in this article represents the opinions of the authors. This commentary in no way constitutes a solicitation of business or investment advice. It is intended solely as an avenue for the authors to express their personal views on investing and for the entertainment of the reader. |

|

Funds operated by this manager: 4D Global Infrastructure Fund (Unhedged) , 4D Global Infrastructure Fund (AUD Hedged) |

8 Dec 2025 - Performance Report: ECCM Systematic Trend Fund

[Current Manager Report if available]

8 Dec 2025 - Performance Report: Bennelong Long Short Equity Fund

[Current Manager Report if available]

8 Dec 2025 - Performance Report: Bennelong Australian Equities Fund

[Current Manager Report if available]

8 Dec 2025 - New Funds on Fundmonitors.com

|

New Funds on FundMonitors.com |

|

Below are some of the funds we've recently added to our database. Follow the links to view each fund's profile, where you'll have access to their offer documents, monthly reports, historical returns, performance analytics, rankings, research, platform availability, and news & insights. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Paradice Australian Mid Cap Fund - Active ETF | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| View Profile | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Paradice Australian Equities Fund |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Antipodes Global SMID Active ETF (ASX: MIDS) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| View Profile | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| ELM Responsible Investments Global Fund | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| View Profile | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

ELMRI ANZ Conviction Fund |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Want to see more funds? |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Subscribe for full access to these funds and over 900 others |

5 Dec 2025 - Hedge Clippings | 05 December 2025

|

|

|

|

Hedge Clippings | 05 December 2025 At the kind invitation of Conexus Financial, Hedge Clippings attended their Professional Planner Researcher Forum earlier this week. Held over two days in the Blue Mountains, apart from AFM, the event brought together a wide range of industry and sector participants (including research houses Lonsec, Morningstar, SQM, and Zenith), asset consultants, platform operators, advice groups, along with many others from the industry. Keynote speakers included ASIC Commissioner Alan Kirkland, industry luminary Graham Rich, and former gold medal-winning swimming legend Grant Hackett, now CEO of GDG, the listed owner of Lonsec and Evidentia. It's fair to say that the major and constantly recurring theme was the issue of conflict of interest (potential or real, depending on one's point of view) against the backdrop of the failure of Shield and First Guardian. However, rather than trying to cover the entire proceedings in Hedge Clippings, we have included selected links below to Professional Planners' own coverage of their event, and would recommend our readers explore further if interested. Commissioner Alan Kirkland, while defending the speed at which ASIC moved to shut down Shield and First Guardian, left no one in any doubt that they will not only be taking legal action against those they believe responsible, but will be following that up with new regulations, although non-specific on what those will be. One has to hope that it will be a practical and measured reaction, although we will have to wait and see in that regard. Insignia Financials' CEO Scott Hartley predicted a chaotic year ahead, thanks to Shield and First Guardian and the regulators' response. All present agreed this combination has potentially created a watershed moment for the research and advice sector, although depending on where one's loyalties, level of conflict of interest, or culpability lies, not everyone agreed on the solution, or in the case of conflict of interest, if they had one! Of interest was Morningstar's impending change to a "pay to play" model, just as ASIC is expected to increase scrutiny on the sector. Graham Rich summed up the issue of conflict nicely by reminding all present why some people rob banks ("it's simple, that's where the money is") while others were heard to comment "no conflict, no interest". We maintain the view that the "issuer pays" model is inherently conflicted and therefore open to potential abuse, even if not by the main participants, then by the bad actors in the distribution chain, including some, such as lead generators, that ASIC claims are outside the regulator's jurisdiction. For our part, we pointed out that while the consumer (advisors and platforms) might want a research report (even if they're not paying for it), the party paying, namely the fund manager, is more interested in the actual rating. Enough! Next week, the RBA meets for the last time this year, and we'll bring you our synopsis of the outcome, thanks to Renny Ellis and Nick Chaplin, from Arculus and Seed Funds Management, respectively. And for those more interested in trivia and comedy than conflicts of interest, today marks the 51st anniversary of the last Monty Python Flying Circus show back in 1974. In our opinion, it was, and remains one of the best, and most groundbreaking comedy series ever. News | Insights New Funds on FundMonitors.com 10k Words | Equitable Investors Is travel becoming the new status symbol for Gen Z? | Insync Fund Managers October 2025 Performance News November 2025 Performance News Bennelong Australian Equities Fund |

|

|

If you'd like to receive Hedge Clippings direct to your inbox each Friday |

5 Dec 2025 - Laffont's Take on the AI Bubble

|

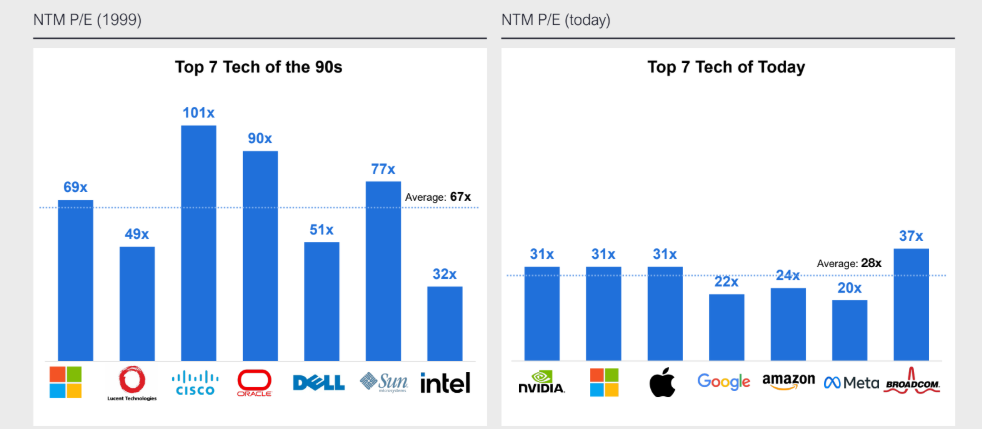

Laffont's Take on the AI Bubble Marcus Today November 2025 5-minute read With Warren Buffett stepping down from public life at 95, younger investors are looking for a new sage to follow. God knows the legendary Buffett gave us enough wise words on life and markets over the years. I'm not sure he can help us today anyway. Buffett's no expert on artificial intelligence, at least as far as I know. He doesn't even have a computer in his office or a smartphone. AI is the new guy's problem. Hunting for a New Buffett in the AI EraWhom to select as a Buffett replacement as the next global sage? Some would suggest Phillipe Laffont might do the trick. He runs a firm called Coatue Management. It now has (approx.) $70bn under management. Laffont's calls on the US tech boom have been prescient for a long time. Last month, Coatue Management released his latest thinking publicly and he addressed the big question of our times: Is AI a bubble, after all? Well, it could be. You can make an argument for the case, and he at least addresses it. Yes, capital expenditure is big. Adoption may not happen on a sufficient scale. The circularity of deals is something to watch for. But Laffont was, and remains, an AI bull. Why the AI Bulls Still Have a CasePerhaps the most compelling point for the bull case, at least for me, is that AI adoption is massive, and yet still so early. There's a long runway here. A further point is that, while the US market is richly valued, it's not crazy, and certainly not like the dot-com boom. You can see how he presents this point below:

Source: Coatue Management We can extrapolate this point further. Much of AI spending is from existing cash flow, at least for now. There isn't the same financial fragility as historic bubbles usually show. Laffont adds that the Big Tech firms may even have lots more cash to splash. That's if a core promise of AI comes to fruition: less labour costs. The numbers around this are quite something. Coatue say that the top 50 tech companies in the US could save $75bn in labour costs annually if AI can reduce headcount by 6%. Imagine what it could do with a higher percentage. All those figures around "headcounts" are to do with human beings, and their livelihoods. There's a big discussion for society to have on this point. But as far as the stock market goes, it leads, all else being equal, to higher profits. Good for share prices. It may not be wise to go against this for too long. Amazon (NASDAQ: AMZN) is already shedding thousands of people. It's usually an early mover on all the big trends. There are no certainties in the markets, or life for that matter. I'm sure Buffett would agree on this point. Bubble Risk vs Opportunity in the Next AI WaveCoatue sees the most likely outcome as AI increasing productivity and GDP. That keeps inflation contained, and, left unsaid, the big US debt problem for another time. Coatue are not blind to the risks. They see a 1/3 chance that the AI bubble bursts and takes the market down with it. But their conclusion seems to be that there's too much potential in the next wave of adoption, such as enterprise AI apps and how AI companies like OpenAI monetise their user base. Don't forget that even a titan like Google (NASDAQ: GOOG) is now under threat here. That should be enough for a lot of companies to shake in their boots... and us watching for the next behemoth to emerge. No moat, a feature so beloved by Buffett, looks safe from the AI encroachment. I can't tell you today what the next wave of AI winners will be. But we won't find them if we don't even look. Rather than fret about whether AI is a "bubble", I'm sure we'll both be better served by looking to see who benefits. That's my takeaway from Laffont's messaging. I'd like to think Buffett might say the same. |

|

Funds operated by this manager: |

4 Dec 2025 - US Private Credit Signals Superior Value Down Under

|

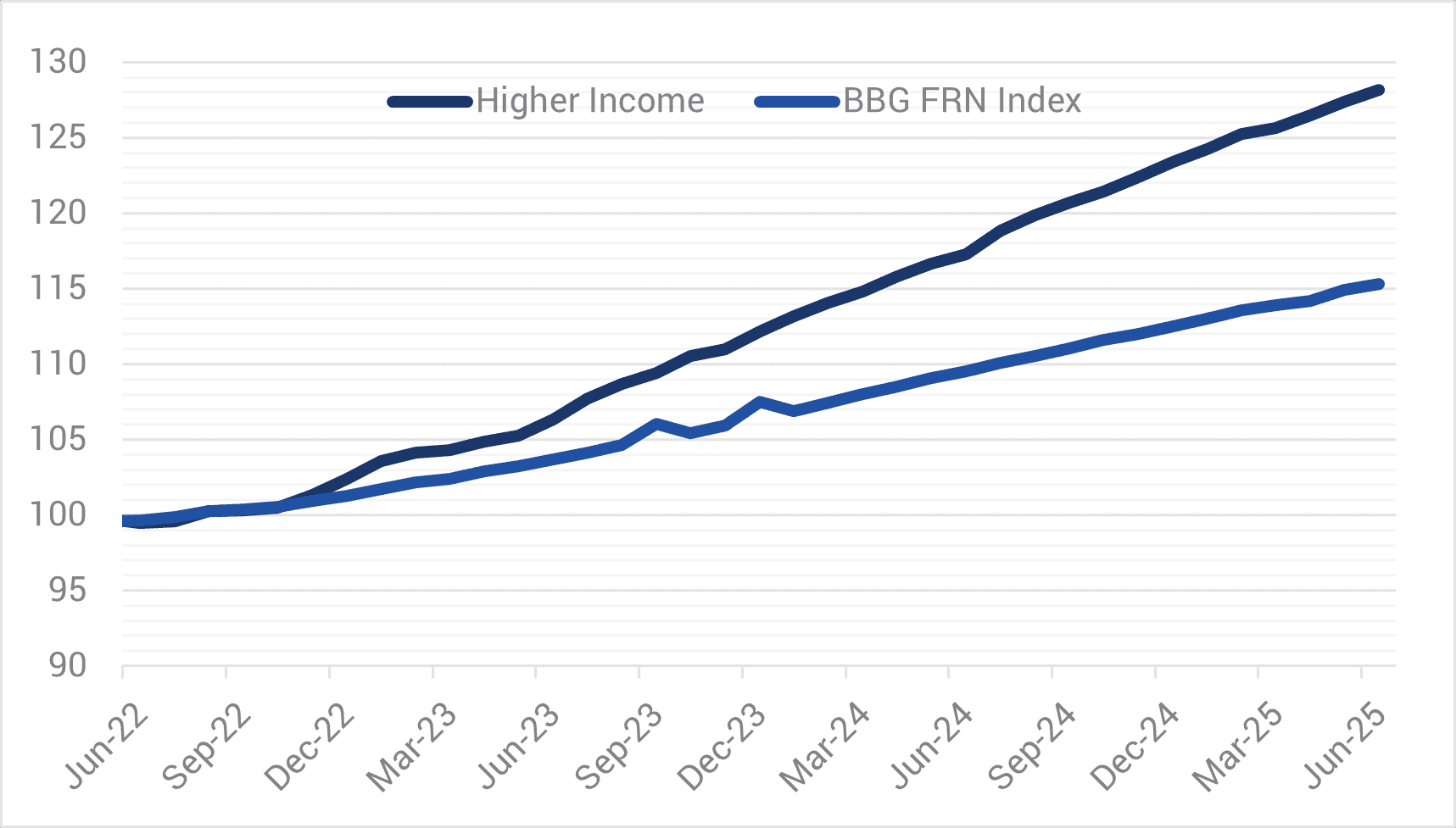

Phil Strano: Is now the sweet spot for active bond management? Yarra Capital Management July 2025 The volatility currently seen in bond markets is being fuelled by a combination of macroeconomic forces. In the U.S., ballooning fiscal deficits and a new $3.8 trillion tax bill are putting upward pressure on long-term interest rates. At the same time, foreign demand for U.S. Treasuries appears to be weakening. Central banks are reducing interest rates, yet are constrained in their influence over longer-dated bonds. Meanwhile, Australia faces a decade of projected deficits of its own, and our yield curve continues to respond more to global forces than domestic settings. These pressures are driving significant steepening in the yield curve - the difference between short- and long-dated bond yields. Steepening curves allow skilled credit managers to adjust risk exposure and capitalize on price differences. In this environment, extending the maturity of our bond holdings has become more appealing, particularly given longer-term bonds can offer stronger price gains as they approach maturity - a dynamic we term "rolldown." At the same time, we're also seeing anomalies in credit spreads, where less sophisticated investors are prioritising yield over relative value, creating pockets of possible mispricing. This is where active management proves its worth. Passive bond funds are bound by index rules. They cannot reposition for anticipated curve moves, nor can they selectively add risk when prices dislocate. Given the Bloomberg FRN Index is more highly rated (average AA- compared to BBB) with shorter spread duration (~two years compared to ~three), the Yarra Higher Income Fund (HIF) is well placed to outperform during risk-on periods (refer Chart 1). However, HIF's outperformance during certain risk-off periods demonstrates the potential benefits of active management. HIF outperformed the index through 2022 in an environment of both higher bond yields and credit spreads and more recently in April 2025. Outperformance in April provides a recent example of how nimble decision-making up and down the curve may contribute to risk adjusted returns. While the FRN Index posted a negative excess return of 11bps compared to the RBA Cash Rate, HIF posted a positive 32 bps excess return despite credit spreads widening by 20-30bps over the month. In April, we started the month expecting volatility around geopolitical events, which prompted us to lift cash levels and position our portfolios with higher overall interest rate duration. Crucially, we also implemented this with a steepening bias or, in other words, a view that long-term interest rates would rise faster than short-term rates. By focusing our exposure on the front of the curve, or short-term bonds, and being underweight long-term bonds at the back end, we were well-positioned when the long end sold off sharply while the short end remained stable. Chart 1 - Cumulative Return - Yarra Higher Income Fund v. Bloomberg FRN Index

Source: YCM/BBG, June 2025.In terms of stock selection, April also presented some fantastic buying opportunities for us to take advantage of spread widening and add high-quality credit exposures at discounted levels. One such name was the USD-denominated Perenti 2029 bonds, an issuer we had previously sold at tight spreads of BBSW+180bps and were able to buy back ~200bps wider (BBSW+380bps). Credit spreads have since contracted ~100bps from these wides, providing a tidy return on investment. While our portfolio positioning has not changed markedly from 12 months ago, these two recent examples show how we're actively managing nimble, benchmark-unaware portfolios that are more 'all-weather' credit in nature. Our April performance, in which both Yarra's Enhanced Income Fund (EIF) and Higher Income Fund (HIF) posted positive absolute returns, underscores the value of our approach. Our strategy came together as a result of preparation, speed, and conviction, none of which are available to passive strategies. Looking beyond the tactical wins, and the case for active credit is supported by the broader macro context. While spread volatility continues, outright yields in the front and mid-parts of the curve have held steady. That means the income on offer remains attractive - and investors are simply being rewarded through a different mix of risk premia. The flexibility to shift between spread and rate risk allows us to preserve capital and position for growth, depending on where the market is offering best value. It's a powerful setup. Investment-grade credit today is offering yields that, on a 12-month view, look comparable to long-term equity market returns - but without the same drawdown risk. Across the spectrum, private credit looks less compelling: the illiquidity and default risk required to justify allocations to private credit simply aren't being compensated in this environment. Looking ahead, we see the drivers of this opportunity set - fiscal overreach, inflation variability, and steepening curves - as persistent features of the bond market over the next 6 to 12 months. We believe this is a sweet spot for credit investing. High running yields and steeper curves, allowing active positioning across durations are compelling and signal the era of 'buy everything and wait' in fixed income is over. Today's market rewards clarity of view, agility of execution, and a willingness to lean into volatility when others step back. |

|

Funds operated by this manager: Yarra Australian Bond Fund , Yarra Australian Equities Fund , Yarra Emerging Leaders Fund , Yarra Income Plus Fund , Yarra Enhanced Income Fund |

Source: 4D, Bloomberg as at 20/11/25M

Source: 4D, Bloomberg as at 20/11/25M Source: Bank of Greece, Federal Reserve Bank of Saint Louis and LSEG

Source: Bank of Greece, Federal Reserve Bank of Saint Louis and LSEG Source: 4D, Bloomberg as at 20/11/25

Source: 4D, Bloomberg as at 20/11/25 Source: Bank of Greece, Federal Reserve Bank of Saint Louis and LSEG

Source: Bank of Greece, Federal Reserve Bank of Saint Louis and LSEG Source: NAB, Bloomberg, Fed Reserve Bank of New York, Macrobond

Source: NAB, Bloomberg, Fed Reserve Bank of New York, Macrobond Source: 4D, Bloomberg

Source: 4D, Bloomberg Source: JP Morgan

Source: JP Morgan Source: 4D, Bloomberg

Source: 4D, Bloomberg Source: 4D, Bloomberg

Source: 4D, Bloomberg

Source: 4D, Bloomberg

Source: 4D, Bloomberg